The State of AI in Insurance (Vol. VIII): Reasoning Models

Executive Summary

- Reasoning is the capacity for LLMs to undertake internal “thinking” before answering a prompt

- Reasoning capabilities are most useful when applied to more complex tasks

- Similar to past findings, our research shows that the performance of reasoning models is directly impacted by the underlying use case

- The choice of reasoning model, and reasoning effort, is determined by factors such as acceptable performance, cost, and latency

From the Editor

For this edition of “The State of AI in Insurance” our data science and research teams dig into the reasoning models offered by OpenAI and Anthropic. Reasoning models are designed to allow the LLM to “think” before providing an answer, theoretically improving accuracy and efficiency on complex tasks.

We began looking into the performance of reasoning models when applied to insurance use cases in “The State of AI in Insurance: (Vol. VI): Claims Decisioning and Liability Determination in Subrogation” where we found that reasoning models performed well against both simple and complex insurance use cases. At the same time, despite the excellent performance observed, the associated cost and increased latency made them less suitable for basic data extraction and categorization tasks.

As we continue our research into the performance of reasoning models and their application against insurance use cases, we are making one important update to our approach by specifically addressing the concept of “reasoning effort”—the ability to adjust the depth of a model’s internal thinking. While this control is present in OpenAI’s earlier o‑series reasoning models, all of our previous testing was done using the medium setting. This report explores the impact of different “reasoning effort” settings (minimal, low, medium, and high) when applied to our core use cases.

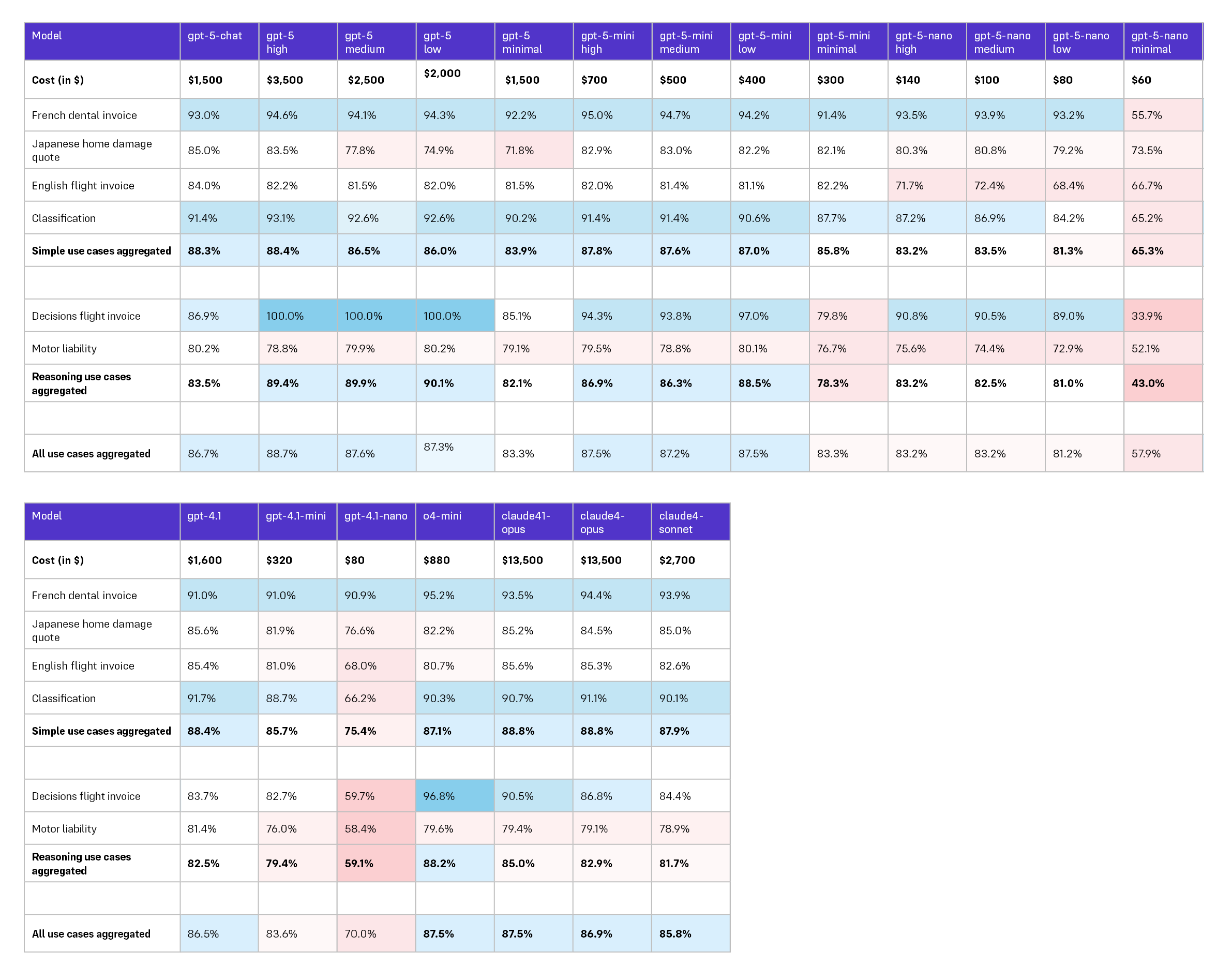

LLM Reasoning Model Comparison for Information Extraction & Classification, Select Insurance Documents

Methodology

The data science and research teams used six test scenarios to evaluate the performance of 10 different publicly available reasoning models. Four of the scenarios are classified as extraction and classification tasks. Two scenarios, Claims Decisions and Motor Liability, are classified specifically as reasoning tasks.

- Information extraction from English-language airline invoices (complex)

- Information extraction from Japanese-language property repair quotes (simple)

- Information extraction from French-language dental invoices (simple)

- Document classification of English-language documents associated with travel insurance claims (complex)

- Claims Decisions (reasoning)

- Motor Liability (reasoning)

Defining the Claims Decisions scenario — can the model make the following decisions:

- Is the claim declaration within the policy’s effective date?

- Is the invoice consistent with the claim?

- Is there any reason to deny the claim based on the claim description?

- Is there any information missing that would be required to make a coverage or reimbursement decision?

- Claim status determination.

- If the claim is covered, how much should be reimbursed in total?

Defining Motor Liability:

- Can the model ascertain, based on the information contained in a claim, liability required for a subrogation determination?

The LLMs were tested for:

- Coverage - did the LLM extract data when the ground truth (the value we expect when we ask a model to predict something) showed that there was something to extract?

- Accuracy - did the LLM present the correct information when something was extracted?

Prompt engineering for all scenarios was undertaken by the Shift data science and research teams. For each individual scenario, a single prompt was engineered and used by all of the tested LLMs. It is important to note that all the prompts were tuned for the GPT LLMs, which in some cases may impact measured performance.

A Note on Costs

For standard models we base our cost estimate related to processing 100k documents on the assumption of 0.5k tokens for the output. For reasoning models, which increases output tokens, we use the following output‑token multiplier in our cost estimates:

- Minimal: 1.0

- Low: 1.5

- Medium: 2.0

- High: 3.0

Reading the Table

Evaluating LLM performance is based on the specific use case and the relative performance achieved. The tables included in this report reflect that reality and are color-coded based on relative performance of the LLM applied to the use case, with shades of blue representing the highest relative performance levels, shades of red representing subpar relative performance for the use case, and shades of white representing average relative performance.

As such, a performance rating of 90% may be coded red when 90% is the lowest performance rating for the range associated with the specific use case. And while 90% performance may be acceptable given the use case, it is still rated subpar relative to how the other LLMs performed the defined task.

Results

Analysis

The GPT‑5 family:

In our testing, GPT‑5 delivered excellent performance on reasoning tasks while lagging on more simple, or structured use cases. Interestingly, these results mirror the behavior we previously observed when testing o4‑mini (a pure reasoning model). Although GPT‑5 is often viewed as a generalist model, in our testing it often behaved more like a reasoning model. As such GPT‑5 remains ideal for use against complex reasoning workflows, but we believe there are better alternatives for when simple extraction/classification is required.

Performance results for GPT‑5‑mini indicate this model is an attractive baseline default for most use cases. Its output quality sits in the same band as strong general models while being much more cost‑effective than the mainline GPT‑5. However, we recommend setting its reasoning effort to “low” by default and only consider “medium” when latency and cost headroom exist. “High” reasoning effort is not warranted.

Finally, while GPT‑5‑nano is appealing based on cost, this model exhibits clearer trade‑offs on structured extraction and decision tasks. We recommend employing this model only in those situations when budget is of primary concern and where quality requirements are modest.

OpenAI baselines and o4‑mini:

Our testing shows that GPT‑4.1 continues to be a reliable option for simple tasks at good value. We also believe that o4‑mini remains a strong reasoning option. However, given GPT‑5‑mini’s demonstrated balance, we believe this model, with reasoning effort set to “low” should be evaluated before moving up to heavier reasoning models.

Anthropic:

Claude 4.1 Opus improves over prior Claude versions but the uplift does not justify its premium for our mix of use cases. Sonnet remains the cost‑sensible choice within the Anthropic lineup.

Conclusion

Shift’s research continues to show that LLM performance, and therefore which LLM is most appropriate for deployment, is intrinsically tied to the use cases to which they are applied. Organizations adopting LLMs must have a solid understanding of acceptable performance parameters, latency, and costs before making a decision about the best path forward. While it may seem natural to believe “bigger is better” we are demonstrating through our research with LLMs that such an assumption is most often false.

-1.png)

.png)